BLOG

SURJ Marin Blog posts

February 6, 2023 || What is systemic racism?

“Systemic racism is naming the process of white supremacy,”

– Glenn Harris, President of Race Forward

To white folks, it may seem like we’ve moved past racism in the liberal county of Marin. But rest assured, it’s alive and kicking. Of course, there’s overt racism that shows up in interpersonal interactions. But there’s another, more potent form of racism that doesn’t get nearly the attention it deserves: systemic racism.

Also known as institutional racism, systemic racism refers to the ways in which racial discrimination is built into the laws, policies, and practices of society and institutions. It shows up as unequal treatment or outright discrimination in criminal justice, employment, housing, health care, education, and political representation. Because it is embedded in the operation of these established and respected structures, it is harder to spot than racism exhibited by individuals. Therefore, it receives far less public condemnation.

What does it look like?

Structural racism tilts the playing field so that it is more challenging for people of color to participate in society and in the economy. While structural racism manifests itself in separate institutions, factors like housing insecurity, the racial wealth gap, education and policing are all intertwined.

One of the most visible forms of systemic racism is in the criminal justice system. Studies have shown that Black Americans are far more likely to be stopped, searched, arrested, and sentenced to prison compared to white Americans. According to the American Bar Association, “African Americans are incarcerated in state prisons at 5X the rate of whites… [and] face disproportionately harsh incarceration experiences as compared with prisoners of other races.” This is not due to a higher rate of criminal behavior among Black Americans. Rather, it’s due to the ways in which the criminal justice system targets people of color and especially Black folks from their first interaction with police through pleas, conviction, incarceration, release, and beyond.

Education is another area where systemic racism is prevalent. Due to residential segregation Black and Latino students are more likely to attend grossly underfunded, overcrowded schools and lack resources, which leads to lower academic achievement. This is not a coincidence but a result of discriminatory housing policies and school funding formulas that have been in place for decades.

Systemic racism in stats:

- Juvenile Incarceration: As of 2013, Black juveniles were more than four times as likely to be committed as white juveniles, native American juveniles were more than three times as likely, and Hispanic juveniles were 61 percent more likely for behaviors that rarely lead to the incarceration of white students.

- Education: Racial minorities have always had limited access to education but one way that shows up systemically is in funding. The richest 10% of U.S. school districts spend nearly 10X more money than the poorest 10%. Money matters a lot in education. It directly impacts teacher quality, curriculum quality, class sizes, and access to computers. Yet the dominant view is that if students do not achieve, it is their own fault.

- Job market: A 2021 study of 100 top employers found that applying to a job with a distinctly black name made someone 10% less likely to get a job compared to the same resume with a more white-sounding name. The top 20% of the firms studied explained about half of the discrimination against Black applicants. People of color, particularly Black Americans, also face discrimination in promotion, which leads to lower wages, fewer opportunities for advancement, and a greater likelihood of unemployment.

- Housing: Structural racism in the U.S. housing system has contributed to dramatic and persistent racial disparities in wealth and financial well-being, particularly between Black and white households. If the trends continue, it could take more than 200 years for the average Black family to accumulate the same amount of wealth as its white counterparts currently hold.

- Environment: Because they often lack political clout and influence, communities of color are disproportionately burdened with health hazards through policies and practices that force them to live in proximity to sources of toxic waste or pollutants such as sewage works, mines, landfills, power stations, major roads and emitters of airborne particulate matter. As a result, these communities suffer greater rates of health problems. A study by the EPA found that Blacks in America are exposed to 1.5 times more disease-causing pollutants than whites.

Systemic racism here in Marin

- Black residents comprise 2.4% of the county’s population, according to the 2020 census, but they made up 18% of traffic stops in the sheriff’s department’s jurisdiction. Most did not lead to arrests or other legal follow-ups.

- In Marin City, a Black person compared to a white person is:

- 50% more likely to be stopped for a traffic violation.

- 3X more likely be stopped for reasonable suspicion of criminal activity.

- 5X more likely to be arrested with or without a warrant.

- 60% more likely to receive a warning.

- 3X more likely to be let go without a warning or citation.

Higher stop rates combined with the higher rate of “no action” tends to suggest that deputies are more suspicious of Black people than white people.

- Marin has a history of redlining, which is an example of systemic racism in housing whereby mortgage lenders denied home loans and mortgages to racially marginalized communities. While illegal today, it contributed to the creation of the mostly white community in Marin that persists today. Many of Marin’s towns, cities and unincorporated hamlets have white populations above 90%, with other small zones like Marin City and the Canal District having populations of mostly African Americans and Latinos – remnants of redlining.

- The California Association of Realtors recently repudiated its 1964 campaign to overturn the state’s fair housing law as well as its history of discriminatory practices. During that time, it was rumored that Marin real estate agents had an unspoken code whereby they would not represent buyers of color – effectively locking racial minorities out of the Marin home market.

- Many property deeds in Marin still contain language that shows how certain populations were intentionally excluded from renting or purchasing homes in all parts of the country.

- Low home appraisals is one form of systemic racism. A recent documentary tells the story of a Black family in San Rafael who sued appraiser Janette Miller of Miller & Perotti Real Estate Appraisers for racial discrimination after an appraisal of their home on Pacheco Street in February 2020 came back $455,000 lower than an appraisal done in March 2019.

- One landmark Supreme Court case in 1944 involved the Brotherhood of Boilermakers, Iron Shipbuilders and Helpers of America in Marin who refused to admit African Americans into their ranks – thus locking them out of well-paying jobs.

- Read about environmental racism in Marin here.

How you can help:

Systemic racism is what people are talking about when they refer to racial minorities as being from “historically disadvantaged communities.” Racism has played an active role in the creation of our systems of education, health care, home ownership, employment, and virtually every other facet of life since this nation was founded (and even before that time).

So what can a single individual like yourself do when the injustices are woven into the fabric of our society through laws, public policies and common practices?

- Start with yourself: To the degree that you are involved in organizations, work to identify and call attention to organizational practices that may tend to disadvantage people of color and/or permit racism.

- Use your vote: Vote for initiatives and candidates that will advance criminal justice reform, fair housing policies, education funding reform, etc.

- Join us at SURJ Marin: Reading this article was a step in the right direction. Join SURJ Marin and start showing up for racial justice right here at home. There’s work to be done.

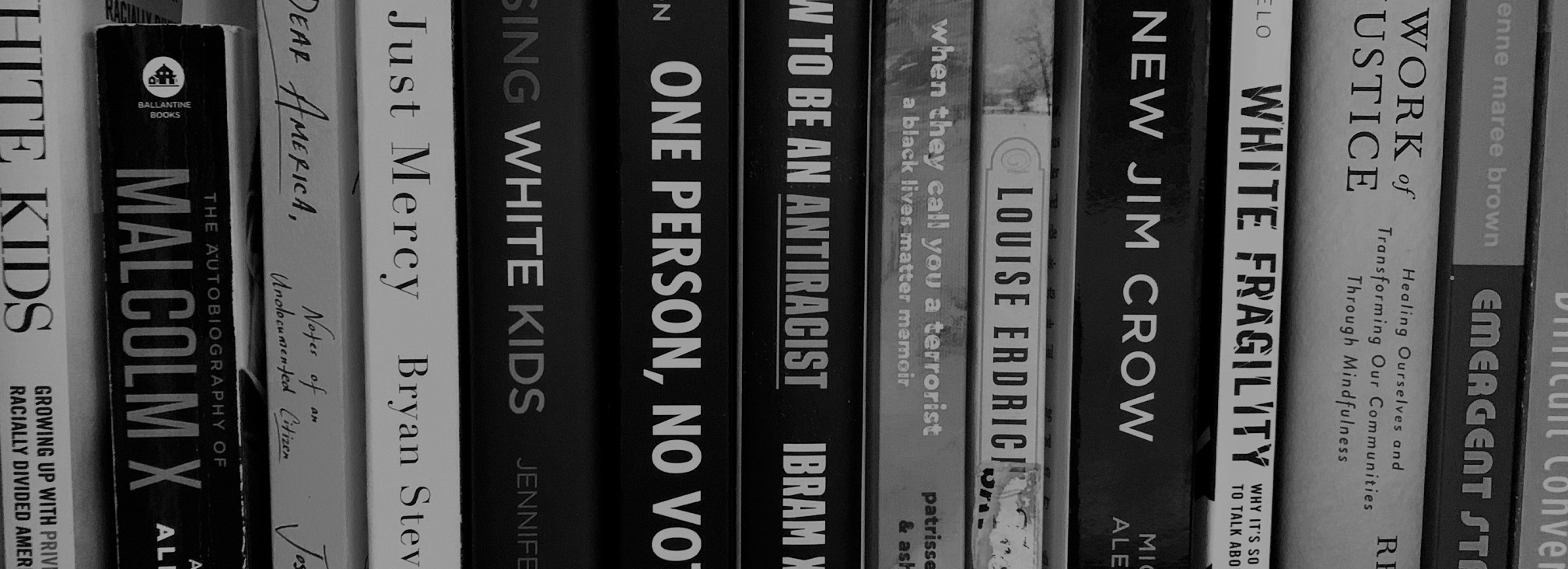

Further Reading:

https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/racial-disparities-in-youth-commitments-and-arrests/

https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/justinphillips/article/police-racial-bias-17494613.php

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/17/realestate/what-is-redlining.html

October 19, 2022 || What is environmental racism and how does it work?

“Tell me your zip code, I can tell you how healthy you are.”

-Dr. Robert Bullard, professor of urban planning and environmental policy at Texas Southern University

A term coined in 1982, environmental racism is a form of systematic racism whereby communities of color are disproportionately burdened with health hazards through policies and practices that force them to live in proximity to sources of toxic waste or pollutants such as sewage works, mines, landfills, power stations, major roads and emitters of airborne particulate matter. As a result, these communities suffer greater rates of health problems. Environmental racism is generally supported by a collection of official rules, regulations, common practices, policies and decisions made by a government or corporation that deliberately targets communities of color for “locally undesirable” land uses and lax enforcement of zoning and environmental laws.

In other words, because the residents of these neighborhoods often have little political or financial clout, it’s far easier for companies and governments to dump hazardous chemical waste or put a heavily polluting freeway there than in your typical white neighborhood.

What does it look like?

Environmental racism was first noticed in the late 1970s, after residents of a Black middle-class neighborhood in Houston, Texas, received the unwelcome news that their little corner of the city would be the future home of a solid-waste dump. “Why here and not somewhere else?” they wondered. So they looked into it and discovered that even though only 25% of the city’s population was Black, 14 of the 17 industrial waste sites (82%) were in Black neighborhoods.

It’s a well-established pattern that systematically harms communities of color.

- Countless studies dating back to the ’70s have shown that minority groups–and Black communities in particular–suffer disproportionately from a slew of environmental hazards.

- A nationwide study conducted in 1987 concluded that the single best predictor of whether someone would live near a toxic waste site was race.

- A study by the EPA found that Blacks in America are exposed to 1.5 times more disease-causing pollutants than whites.

- Communities of color who live near industrial agriculture are home to lagoons of pollutants and waste that produce hydrogen sulfide and drive up miscarriages, birth defects, and disease.

- Living in toxic conditions can also cause cancer, other forms of reproductive harm, and respiratory illnesses such as asthma.

- Because of their high exposure to environmental contaminants in the air and water, people who live in communities of color have a higher incidence of co-morbidity and therefore an increased likelihood of dying from COVID-19.

- EPA studies have repeatedly found that race is a more reliable indicator of proximity to pollution than income alone. These are the neighborhoods that people of color were forced into through discriminatory housing policies (i.e. by excluding them from other neighborhoods and denying their loans – aka redlining).

There are thousands of examples in the Bay Area

- A 2021 study found that in West and Downtown Oakland, where more than 70% of the population is people of color, up to 1 in 2 new childhood asthma cases were due to traffic-related air pollution. By contrast, in an Oakland Hills neighborhood where more than 70% of the population is white, the fraction of childhood asthma from pollution is much lower—about 1 in every 5 cases.

- In Oakland, a ban on heavy trucks on Interstate 580, which runs through predominantly white neighborhoods, essentially redirects this heavily polluting traffic to Interstate 880, which is surrounded by predominantly BIPOC neighborhoods. Kids in these neighborhoods suffer higher rates of asthma hospitalizations.

- In predominantly BIPOC Marin City, the community suffers from cracked lead-based water pipes, a lack of drainage pipes at the entrance to Marin City and pervasive contaminants from the highway.

How you can help

The “Right To Health,” defined as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,” is written into the World Health Organization’s founding document as a basic human right. It further asserts that the “Right To Health” is for all people WITHOUT distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition. Fixing the problem of environmental racism is the moral and ethical thing to do.

- Practice self-education. Start keeping an eye out for instances of environmental racism and educate yourself about the issues at the local level. It’s here in Marin.

- Elevate the voices of impacted communities. Seek out environmental justice organizations that are working to protect these underrepresented people. Follow them on social media, retweet/reshare their posts, and give to their causes.

- Learn about and support https://anthropocenealliance.org/marin-city-climate-resilience-and-health-justice/

- Hold your representatives accountable. Sign the petitions (they do make a difference).

- Use the power of boycotts. If you know of companies that are benefiting from environmental racism, stop buying their products and encourage your friends to do the same.

Further reading

- Environmental racism defined (Wikipedia)

- What is systematic racism? (aka institutional racism, Race Forward)

- What is environmental racism and how can we fight it (World Economic Forum)

- The complicated history of environmental racism (University of New Mexico)

- The complex story of environmental damage in SF’s Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood (Stanford)

- Clean & White: Environmental Racism in the United States (bookshop.org)

- Race, history, ecology and design in the SF Bay Area: A Marin City case study (Kristina Hill, Director of UC Berkeley’s Institute for Urban and Regional Development (IURD))